With Colorado’s lawmakers considering an increase in penalties for fentanyl possession, one thing is certain: Doing so will hit communities of color hardest — exacerbating the mass incarceration crisis of Black Coloradans; making it more difficult to find employment, housing, and education; and marking another counterproductive chapter in the failed War on Drugs.

While Colorado lawmakers have taken steps in recent years to reverse some of the state’s harshest, most punitive policies and correctly moved towards treating drug use as a public health crisis rather than a carceral issue, the recent legislative proposal to make fentanyl possession a felony threatens to roll-back progress, undermine racial justice, and disproportionately harm Colorado’s communities of color.

Under the proposed bill, which passed the General Assembly last week and is currently up for debate in the Senate, possession of a gram or above of any drug with even a trace amount of fentanyl will be treated as a felony. The bill also ramps up criminal penalties for distributing the drug and sets aside funding to pay for overdose antidotes and testing strips, expand the state’s harm reduction program, and develop protocols for treating withdrawal symptoms at correctional facilities. Providing resources to proven harm-reduction solutions, it’s a proposal that takes a major step forward before erasing that progress by punishing people with a substance use disorder with time behind bars.

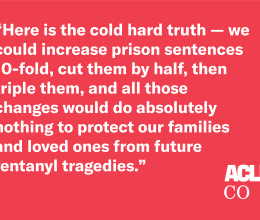

The criminalization approach ignores years of research showing that threatening to punish drug users is not effective. Hours and hours of testimony from medical professionals have shown that the changes to brain chemistry that occur during chronic drug use make users less able to register consequences like legal threats. Simply put, we already know criminalization does not work – so why would we go down that failed road again?

While people across the state use drugs at a similar rate, Black people are twice as likely as white people to be arrested for a drug offense. By the same token, innocent Black people are twelve times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of drug offenses than innocent white people and serve longer sentences than white people for similar offenses.

Long-term substance abuse recovery depends heavily on stable housing and employment, both of which become substantially more difficult to find with a felony conviction. Increasing punishments is likely to lead to more overdose deaths, more pain, and more suffering across the state as drug users avoid health services and instead resort to riskier drug-using behavior to avoid detection and prosecution.

Most people recognize the perils of going back to a system that criminalizes drug users rather than providing the supportive systems they need to recover. That’s why in recent polling a majority of voters support decriminalizing the possession of a small amount of drugs, opening overdose prevention centers, and increasing access to medications to reverse opioid overdoses.

Fortunately, we already have evidence about what types of treatment approaches are most effective. Many of these supports are included in the current draft legislation. These include allocating resources to meet the demand for substance abuse treatment rather than trying to imprison our way out of the problem. In addition to funding community-based organizations to help prevent addiction in the first place, we must vastly expand our investments in treatment, recovery, and harm reduction strategies. To solve this public health crisis together, we must treat it with the evidence-based approach it demands. For all Colorado’s families and communities — and particularly for communities of color — reverting to a criminalization model is not only unjust, it’s counterproductive and dangerous.

Deborah J. Richardson is the Executive Director of ACLU of Colorado, where she works to defend the civil liberties and civil rights of all people in Colorado.